Grain

Kenter Creek is the formal name for the storm drain that debouches right where I have been making my sculptures, but the lifeguards call it Cancer. Those who staff Tower 18 have about double the incidence of skin cancer occurring elsewhere. Sewage spills fill Ballona Creek, four miles south. After a rain the water smells like eucalyptus, engine oil and trash instead of salt. In February of 1987 I write a letter to the editor of the Los Angeles "Reader" expressing my desire for clean water, and after that hang up my sand tools. All I have left is memories and three albums of photographs.

With sand closed off, I take up other interests. I try a few sculptures in clay and plaster, but it's not the same. It's not even close. I do some mountain biking. Eventually wanting longer legs, I start riding my motorcycle, each ride taking me farther afield. The explorations open my eyes to land once seeming desert, showing that it has great beauty. I also start hiking in the nearby mountains with a coworker and find even more beauty in close looks along the trails and rivers.

When I lived in Maine, my friend Robert and I used to go walking around the mountains and shoreline. We'd do cooperative photography, shooting until we ran out of light and then sending the film off for processing. The film came back, I'd make some apple crisp and we'd look at slides, critique them, and eat too much. We also talked of cameras and film, dreaming of having the money to buy better equipment as we looked at ads from places in New York.

Writing is cheaper. In those days all I needed was a pen and paper. When I started going to school I soon bought a better tool: an Osborne 1 computer that ran Wordstar. Now that writing was easy I did more of it, and didn't care that there was no audience for the files that stayed on my floppy disks. I enjoyed the process.

One day I discovered the computerized bulletin board system. There were many of these, including several in the city where I lived. The idea of exchanging messages with other people was fascinating but the ideas that passed back and forth were banal. In an attempt to shake things up, I wrote a provocative message and then used a little BASIC program to turn it around backwards. One man responded... and we developed an unlikely, word-based friendship. He was my audience and I started writing little stories about events in my life. The exchange was brief. Warlock became uncomfortable with this kind of interchange and simply disappeared. I, however, was hooked. What is writing without an audience? I moved to Los Angeles and tried to forget about this.

I moved to Los Angeles for a job. Somehow, I had to get to work and other places. A co-worker sold me a motorcycle and I discovered something that handled like a bicycle but could go much farther. Eventually I ended up owning a good motorcycle and riding it all over southern California.

One night I got an idea, and logged on to Compuserve, where I searched for a motorcycle forum. There was one, and I discovered that motorcyclists like to write, and read, stories about their rides. They were looking for an outlet, just as I was, and Compuserve provided it. I started out writing short articles for the forum, but rapidly outgrew that format and switched to Emailing the stories to the other riders. We all shared our stories, and let others see where we'd been through one another's eyes.

Some things, though, can be better described in a picture than in words. There were a few examples of this in the motorcycling magazines, and my interest in the illustrated story, sparked by the 1984 introduction of the Macintosh but buried since then in various other things, came back to life. I get to thinking about photography again, but I haven't touched a camera in years. Shortly, after a strange collision of money, time and happenstance, I own my dream camera, a Pentax 6X7, of all those years ago in Maine. It promptly starts teaching me things.

The first lesson is about mass production. Mass-market photo processing is cheap because of the quantity and competition. When I went to medium format I left all that behind and processing became much more expensive. The first 8X10 print I had made, of a shot taken on a hike, showed me it was also much better.

There's a photo lab just down the street from me, a couple hundred feet away. My neighbor tried to drop two rolls of Kodacolor there for processing, but they didn't do C-41. One day, I walk down there just to find out what the outfit does. It turns out "the outfit" is one man, and he does everything but process color film. As a test, I give him the same negative for that first 8X10; the results were spectacular.

Steve showed me what a real print looks like. It's what I'd been missing for years. All the mud was wiped from my photos and the colors shone clear and sharp. Naturally I went back for more enlargements.

Not so naturally, we struck up a relationship that went beyond the norm between a client and the provider of a service. I walked through his door looking for good prints. He had samples hanging on the wall; seldom am I interested in photographs. Steve's were different. I walked out with ideas and knowledge I'd not had before.

To me, photography had always been a way of recording things. Places, people, personal history. Art photography is highly idiosyncratic and most of it left me cold. It was far too simple and organized, looking like something Kodak would use for advertising. Tasteful, balanced, and with all the life of yesterday's newspaper. Sometimes it was just incomprehensible; the communication bypassed me.

Steve's photos, like a few others I'd seen, snapped. They had tension. They demanded more than a passing glance; there were details there to be noticed in repeated viewings. He experimented with light. The results lived there on his walls. We got to talking about photographs and compositional tension. He was surprised I noticed.

He did a lot of work in black and white. I appreciated his results, but was still a confirmed color photographer. Why limit myself to shades of grey? We kept talking about it, though, on those evenings back in the inner sanctum.

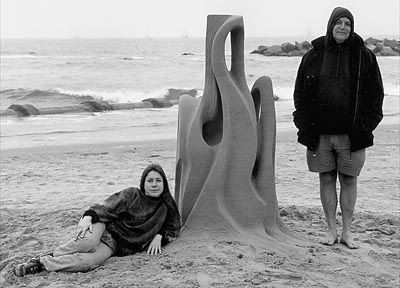

In the general sharing of artistic endeavor among Steve, his wife Virginia and me, eventually I mentioned sand sculpture. It being easier to show what I do than to talk about it, I brought one of my 10-year-old albums down to the lab on one of my many trips.

Most of the time, people leaf through the books idly, rapidly. This was different; Steve went off the deep end. "This is fantastic. When are you going to do another one? I want to take some photos." I was embarrassed.

Now, I hadn't done a sculpture in over seven years. The sea was dirty and my equipment was parked in the garage, dusty. Various people have been working hard to clean up the water; I'd been swimming with friends a couple of times and it actually smelled like seawater. Once Steve started talking about photography and sculpture, I realized the itch was still there. It got stronger. So, one day, I rode along the beach bike path looking for good sand. I found it in Venice.

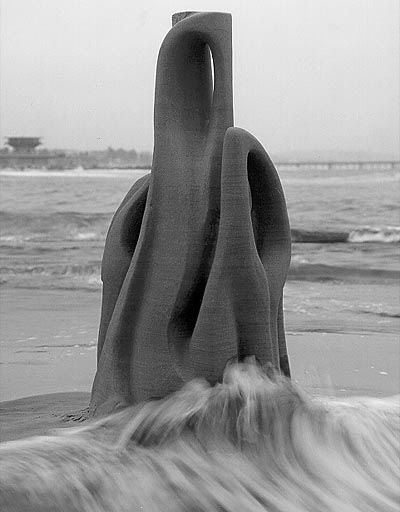

June, just before midsummer's day. Moon-influenced water has receded, leaving me a level place to work. All the usual tools are in place, carried down here on my bicycle. Even Bruce, the lifeguard I met in 1984, is here. Past and present collide, ringing. My skills are rusty but still functional and there's this four-foot smooth arched structure on the beach. I haven't forgotten. When I'm finished, I take some time for photography, this time, at Steve's urging, on black and white film.

With the change in film there's also a change in attitude. The sculpture exists for itself, and satisfies my urge to make things I feel are beautiful. Now I walk around the sculpture, camera in hand because I forgot my tripod, treating it as something to be photographed. I'm playing, looking for interesting angles and shapes under the hard hot sun.

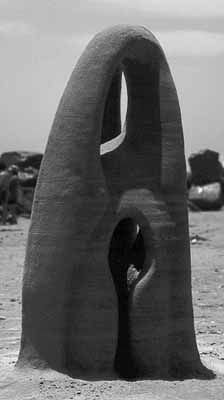

The year's second sculpture starts a new pattern. Some of it copies the old: same equipment, same basic technique. The forms have changed, though, becoming more shaped. Instead of a plain arch, now the arch's legs have a form themselves, gently twisting or concave merging to convex as they rise. With my camera on a tripod, I make a complete circuit of the work and then photograph some details, playing again. When Steve makes a large print from one of my negatives, I'm hooked.

In monochrome silver, the sculpture shines as a form. It bypasses the literalness of color, making an iconic distance, allowing me to see the shape. It's fascinating.

Next: Art