Development

A year passes, warm fall running into cold winter. School runs into a rock and sinks, leaving me trying to figure out what to do with myself as winter grudgingly yields to spring. The school doesn't invite me back, and my roommates suggest I should find another place to live. I put my stuff into storage, rent a one-way car and head west.

In Denver I build some things for my sister. There's time for bike rides, one to Cherry Creek looking for sand. It's coarse. I content myself with more bike rides and walking in the mountains. My friend in L. A. wants me to visit, but I'm having fun in Colorado, in no hurry. Finally she prevails and I catch a plane west, computer and backpack in hand. Los Angeles is the paradigm case for the last place on earth I'd want to live, but financial options are few.

When I was in L. A. in 1982, I took a test for a job with the City. Arriving in 1984, I told them I was available. Then I just had to wait. The beach called. At first I used the equipment I had: two hands and a spoon. Having tasted alternatives in Nebraska, I went to work making better tools.

Whatever they were, they had to be cheap and portable. Anne had a five-gallon bucket for carrying water. A lumber yard sold me some scraps to use for stakes to support I'd conceived: a cheap plastic ground cloth wrapped around the stakes. To hold it together, I had a ball of string. I loaded this kit into Anne's car and headed west.

I thought the string would hold the plastic, I thought the sand would stay put, I thought... but there's no substitute for real experience. The experience failed miserably. The plastic sagged as soon as I tried to put sand in it, pushing out between the spiraling string. I scrapped the attempt and went bodysurfing followed by a free-pile sculpture. Back to the drawing board.

Obviously, the form material had to be stiffer. Couldn't be wood, though, because that's too bulky. Wandering around on Broadway one day, I went into a fabric store and found some Naugahyde upholstery material for half price. Once the light of day shone on the material I understood the price. The lumber yard sold me some laths; I cut a 12-foot piece of the bilious yellow material and glued laths to it every eight inches or so, to stiffen it. When finished it rolled around the stakes into a bundle about eight inches across.

I returned to the beach, carried my kit to the sand and went to work. The stakes, each about five feet long and an inch square, were driven into the beach in a circle. The Naugahyde form wrapped around them, and string wrapped around that held it together. So far so good. Then I started throwing buckets of sand into the form, followed by buckets of water. Another long stick got used to stir and tamp the sand. Repeat for an hour or so, and the form is full, all four feet of it. I untied the string, collected it onto a stick, removed the fabric, pulled out the stakes. Half the pile promptly fell over. Thinking about it, I realized that four feet of wet sand is very heavy. The sand underneath shifted, the pile split.

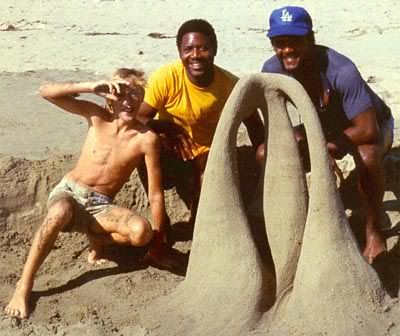

There was still half a pile. I cleared away the waste and started carving. It turned into three graceful curved tapering towers supporting arches. I'd learned something of forms, but nature also has a voice in sand sculpture. The tide almost got it, but some passersby pitched in to build a seawall so I could finish. Then I used Anne's Baggieflex—a Pentax Auto 110 carried in a plastic bag—to photograph the castle and the people. I would have been content to just make the piece, but Anne wanted to see what I was doing.

The experiment worked well enough that I went out to try again. Having thought about what happened with the second effort, for the third one I prepare the beach to hold the weight by wetting it and then doing a stamping dance until my feet no longer leave prints. The form works again and this time the whole pile stands, entire, cylindric. Another hurdle passed, and I also don't have to worry about tide because I've consulted a tide table and built out of its reach. And then parts of the sculpture fall off. Small parts, yes, but I still learn that an intact sculpture stands on a narrow divide between art and engineering.

The attempt is fascinating. It's free and freeing. Never before have I been able to engage in art. Half of the fourth attempt goes on the ground as soon as I unwrap the form but the remaining sand suggests some things, and I carve a succession of leaning arches, long tense curves leading upward to rounded tops. A fellow who'd been sitting behind me, watching, for some time comes up and places the origami bird he'd made in one of the openings. Some surface embellishment makes the whole thing look wind-blown and very graceful. I like it.

I had been thinking that this would be like every other project in my life. Once I solve the technical problems they become boring, and I'm no good at production. I figured I'd go out, make a few sculptures and then run out of ideas and stop. As I look at this sculpture, entirely unplanned yet beautiful, a shiver goes down my spine. Making this sculpture has suggested many more. What if I did this? Or this? The future opens out.

Determined to solve the pile failure problem, on the next effort I scrape away the dry surface sand to reach the damp sand beneath and then pack that with water. The pile holds, but the sculpture is down in a hole rimmed by waste sand. What could I do about this? How about building a raised base? Can I pack it well enough?

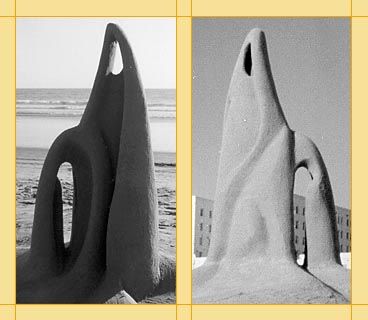

One day I decide to try it. I scrape the dry sand into a heap and then pour water on it, building it up in layers to about six inches tall, a broad frustum. I erect the form on the flat top and fill it. The pile splits after being unwrapped. In the remnant I carve a tall, thin, graceful structure that reminds some passersby of a cathedral. I tell them I didn't have that in mind because I don't believe in God. They tell me they'll pray for me.

The sculpture is tall and elegant, rising proud from the beach. The waste sand gets pulled away, sloping down, and the effect is great: a low conical base and then this sudden eruption of vertical sand. The idea works but needs better exectution. This is always important to learn: did something fail due to bad concept, or bad technique? There's nothing theoretically wrong with the raised base.

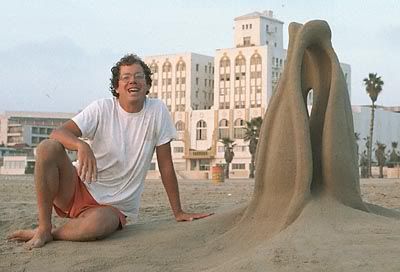

Basic technique has been established. It's mid-fall, late October or thereabouts. I build above the high tide line so I have plenty of time. I carry the water from the sea, up the beach, pour it into the form. If I time it well, the tide is high so I don't have to carry water so far. But it can't be too high, because the sand from down the beach is finer, so better for carving. I carry the sand up to the form and throw it in. Some days I don't have enough energy to do this, so build closer to the tide. After I get a tide table, it becomes possible to suit building location to my energy level. Gradually, as autumn moves imperceptibly into what passes for winter here, all that relocated sand builds a noticeable knoll right on the beach's cusp at the high-tide line.

Sand sculpture is made of the feel of the sand. The waves come and go, wind blows and I work. From some deep place comes this shape that lives briefly and then disappears. Photographs miss that. They're static, flat, lifeless. They don't contain the feel of the sand grains or the calls of the gulls or the feel of wind-driven spray. All they do is show the most basic elements of a form: patterns of light and dark on paper. I shoot them for friends, but within my mind is a much more detailed representation.

The photos have to go somewhere. It does no good to leave them in envelopes, so I buy some inexpensive albums and start putting them in there. How do I differentiate them? The sculptures need names or something. Eventually I decide on numbers and a letter. The first two numbers are the year, then a letter denoting Form or free-Pile, then a serial number for the year. At first I only gave numbers to finished sculptures, but finally decided starts should get a number. Other codes indicate why a sculpture didn't get finished: CCF for complete construction failure, CPF for complete pile failure. Partial failures go to completion, with a PCF indication. All this helps me remember what I did, years later.

The unthinkable happens: the City hires me. I'm to report December 10. I've done about twelve castles. Anne is chiding me about that name; seems what I do has gone beyond the castle that spawned the idea. I'm loath to call them sculptures; that seems too serious but there is no other term that fits. What else could I call them? They become sculptures. Gainfully employed, I wind up going to the beach on weekends. It seems like a different place. Lots more people asking questions.

People are an interesting part of the process. They walk up and ask "What is it?" I tell 'em it's a fantasy, whatever they'd like it to be. Some of the people are regulars, like Bruce the lifeguard. People see what they want to see. A couple comes up from some church, tells me that I will soon be saved. They see it. I don't have the heart to tell them I've already been saved once, and threw it over. A priest sees a cathedral. Joggers go on by. Some of them look, some of them run a circle around me, some of them just plain stop. High compliment. On weekends, I discover it's hard to get anything done for all the questions.

The pattern evolves. Go to the beach, make a sculpture, take some photos, go home. For a few trips, I have to use the bus. Then I learn how to attach all my stuff to my motorcycle. Years go by, 1985 turning to 1986, and that passes into 1987. My skills develop.

With them, photography develops into a little more than a pain in the neck. After all, although I have felt the sand pass through my fingers and the damp wind in my hair, what makes the memory unique is the shape of the sculpture and the photographic paper's memory is molre accurate than mine. My relationship with Anne came apart in an ugly way but each photo I take of a sculpture or look at later is her legacy. What started as habit turned into a part of the process.

At the end of the day, when the sculpture is cleaned up and the base area landscaped, I start doing more thorough photography. A full walkaround of 12 photos, more or less. Once, I even washed my hands many times to take photos of the sculpture in process.

And then, like the mistimed tide rising to take out a work in progress, other aspects of my life undermine the foundation needed for art. I simply quit. The form is rolled up and standing in a corner of the garage, gathering dust.

Next: Grain

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home